To Seventh-day Adventists, the prophecy of

Seventh-day Adventists believe that “the command to restore and to build Jerusalem …” in

When one studies the history of the restoration of God’s people from Babylonian captivity by the Persians, it will be seen that Persian Kings gave three or possibly four decrees. Which one then is the decree God intended should be used as the one from which the time calculations should begin? A study of each of these four decrees will make it clear which is the correct one.

In the first year of his reign, Cyrus gave the first decree, which was 538–537 BC. (See

The second decree of Darius the Great is not dated in Scripture at all, so it is not of any use to anyone. All we know is that it was given in the early years of his reign because, as a result, the rebuilding of the temple was completed, and it was then dedicated, and we are given dates for both the beginning of the rebuilding program and for the dedication. The rebuilding is dated in

This decree is not of much use either. It is even vaguer than that of Cyrus, and logic would require that if God intended either of these decrees to be the correct one to begin a prophecy as important as the 2,300 days, He would have seen to it that the details needed were recorded in the Bible.

For this decree, we had recorded the dates when Ezra left Babylon with the decree and when he arrived in Jerusalem, and the decree went into effect. These details tell us that Artaxerxes issued the decree in the seventh year of his reign, and this information is recorded in

Furthermore, we are told that this decree made mention of the restoration of local government on a scale note mentioned in the other decrees. Note

However, perhaps the greatest argument of all is that when the date for this decree 457 BC is taken as the beginning date, the prophecy reaches the baptism of Jesus when He was anointed, and thus became the Messiah (Messiah means the anointed One). This is the decree God intended us to use. He gave us details about its date and when it went into effect and then about the baptism of Jesus on time, puts the seal of authenticity on it. It is just too accurate to be wrong! One thought found in

Nehemiah was appointed governor in 444 BC in the twentieth year of Artaxerxes (

Therefore, the only conclusion is that the decree God intended is that of Ezra 7—the seventh year of Artaxerxes, which was 457 BC. Some books indeed give 458 BC as the date for this decree, so we will now set forth evidence to show that it was 457 BC

Before we can find which is the seventh year of Artaxerxes, we will need to become familiar with the calendars used by the people who lived at the time.

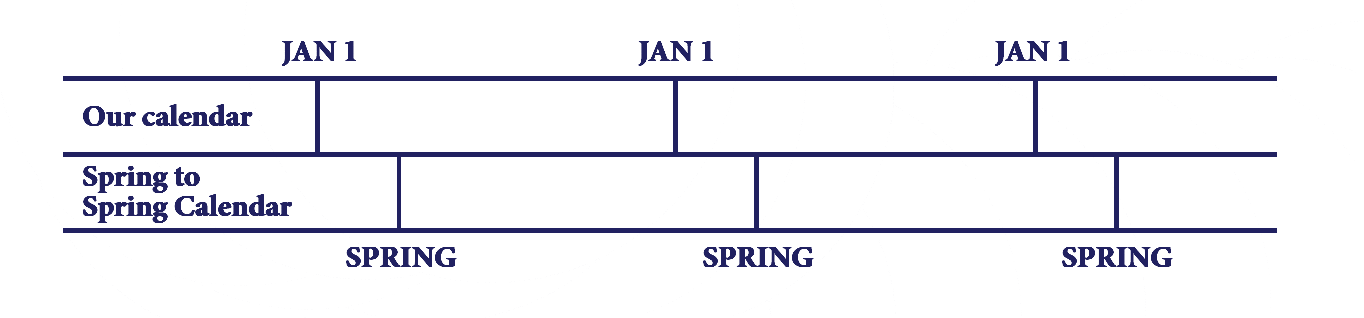

The calendar we use came basically from the Romans. It begins on January 1 and ends on December 31. No other people of ancient times used this calendar. It is sometimes called the

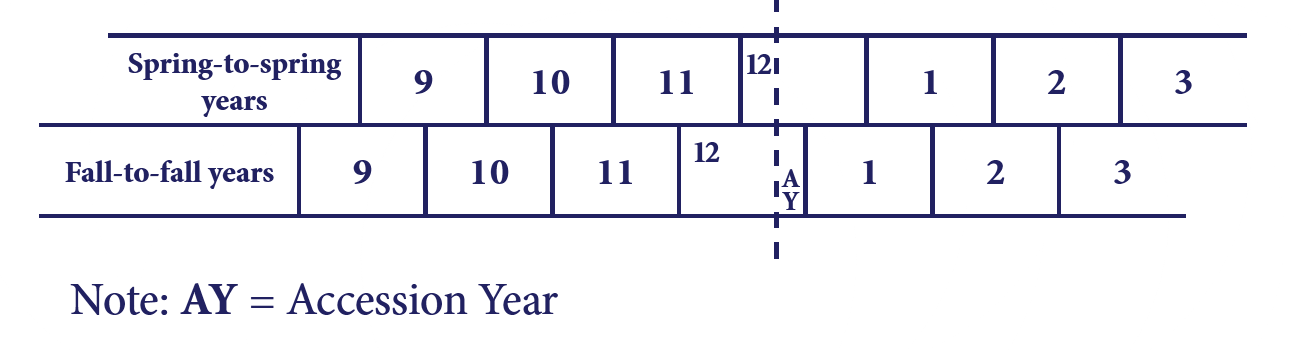

The Babylonians, Persians, and the Jews, as far as their religious year or religious calendar was concerned, used a spring-to-spring calendar. Spring in the Northern Hemisphere begins around the beginning of April. Thus we can show the following pattern. Our calendar is shown with the spring-to-spring (Northern Hemisphere) calendar.

If a spring-to-spring calendar is used for Ezra 7, we get 458 BC as the date for the decree. However, we know that the Jews also used a fall-to-fall (autumn-to-autumn) calendar when counting the reigns of both their own and foreign kings. When this information is recognized, the date is 457 BC. We will now set forth three lines of Bible evidence to show that the Jews had used this fall-to-fall calendar at times.

1. Example from the Reign of Solomon

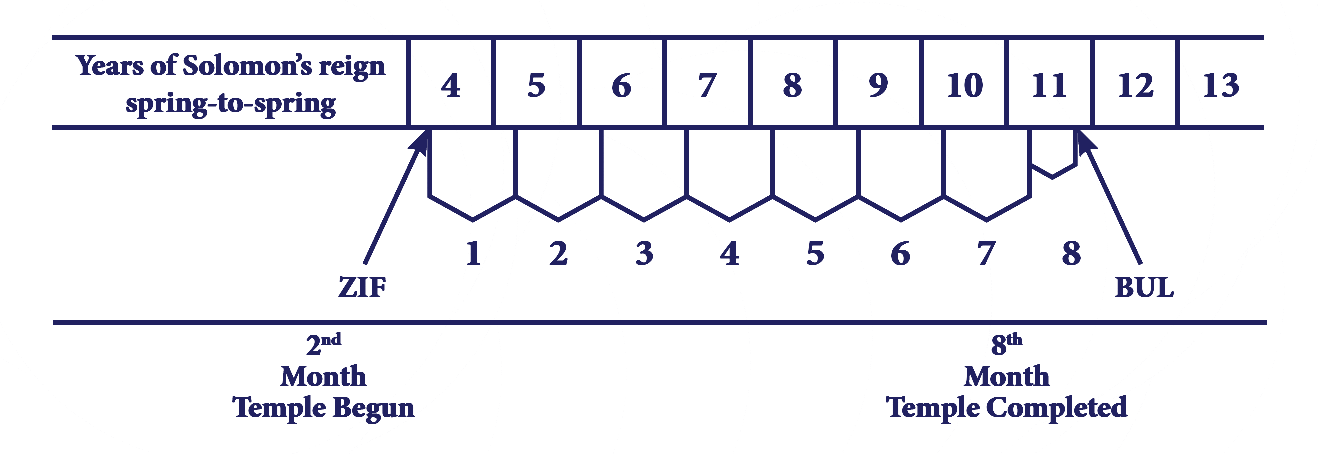

Now with these facts, let us see what happens when we use a spring-to-spring year.

The building of the temple on a spring-to-spring year would have taken eight years—7 .5 literally, which the Jews would have counted as eight years with their inclusive reckoning. Hence the spring-to-spring calendar does not fit the facts the Bible has given us.

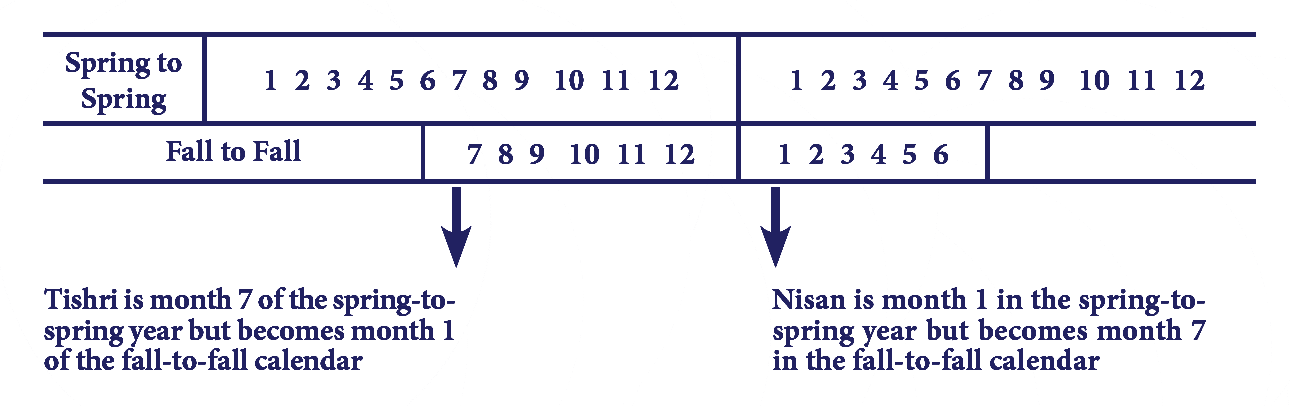

Now let us consider the Jewish fall-to-fall calendar and see if it fits the facts. It should be pointed out that the spring-to-spring calendar is the calendar that decides the order of the months. Thus Nisan, which is the first month of the Jewish spring-to-spring calendar, becomes the seventh month in the Fall to Fall calendar. Tishri, the seventh month of the spring-to-spring calendar, becomes the first month of the fall-to-fall calendar. The following diagram explains the relationship. Months are shown by numbers based on the spring-to-spring calendar.

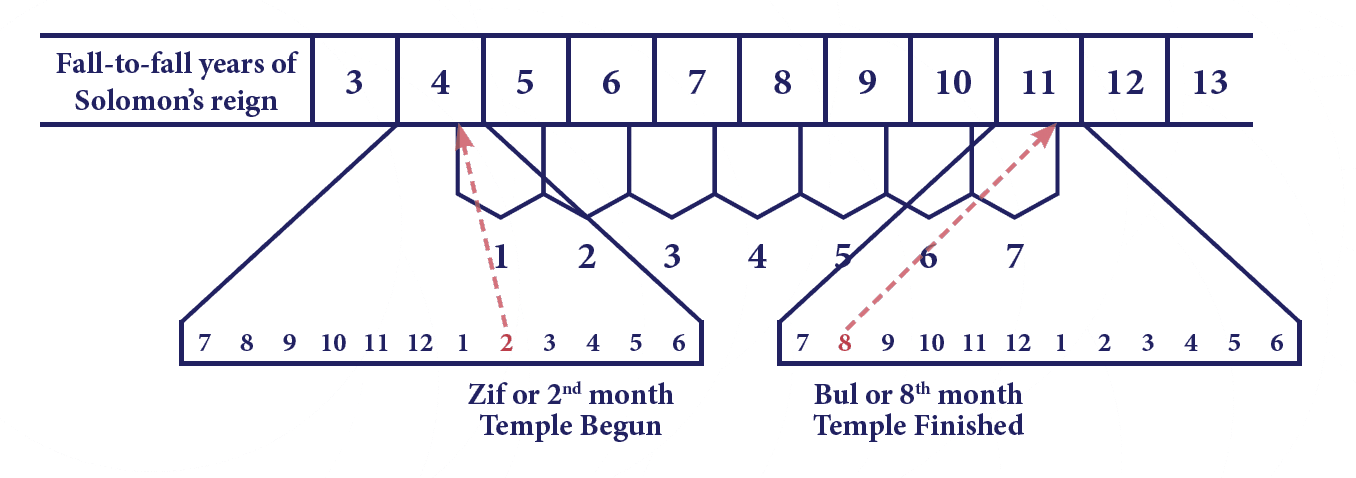

Perhaps the best comparison we can make to illustrate this relationship is to compare the Australian financial year or taxation year with our calendar. January is our first month, but it is the seventh month of the Australian financial year, which runs from July 1 to June 30. Thus, as shown above, whenever a fall-to-fall year is shown the order of the months is always 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, thus following the order of the months of the Spring to Spring year. Now we shall show how this applies to the building of Solomon’s temple.

Note that the fall-to-fall reckoning, as shown above, comes to SEVEN years, as the Bible says. Hence it is clear that a fall-to-fall calendar was used in counting the reign of Solomon.

2. Example from Josiah

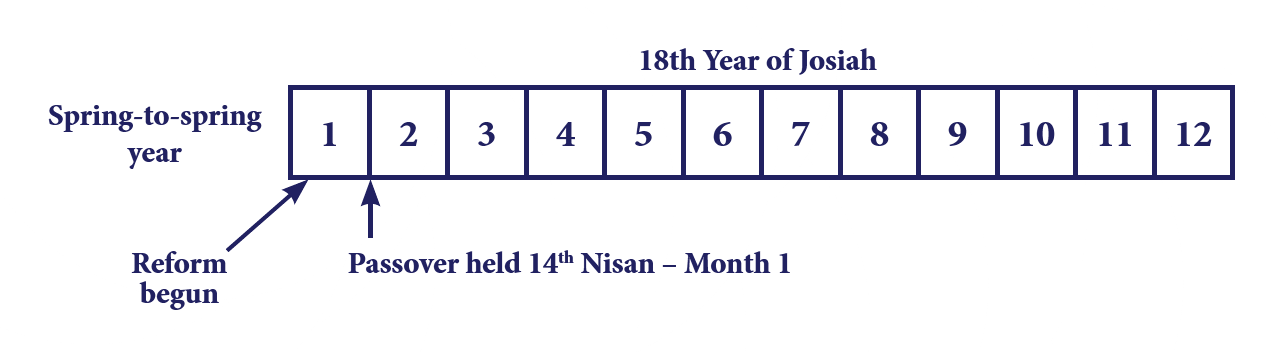

In

Now let us see how this would fit into a spring-to-spring year

Thus the maximum possible time in which all this could have been effected would be 14 days, and this is certainly not enough time. Note that the reforms were begun in the eighteenth year, the same year the Passover was held.

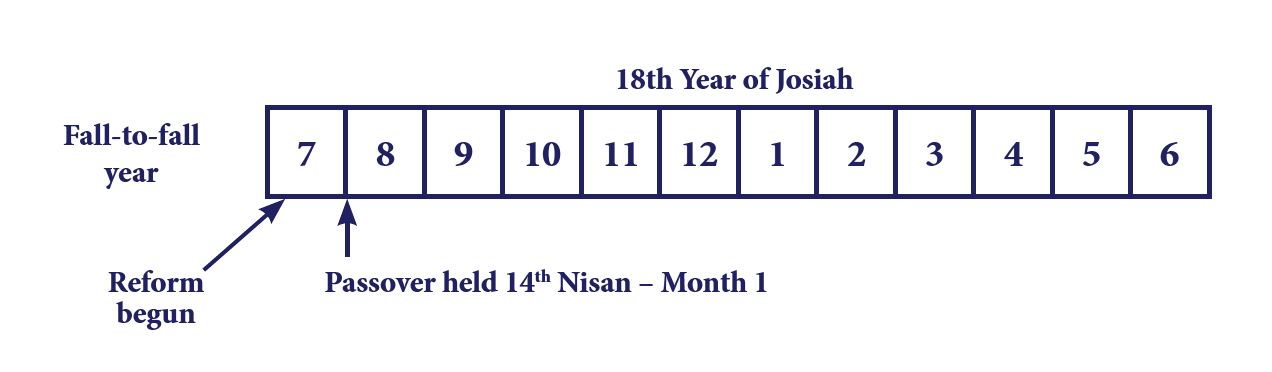

Now let us see how the evidence fits into a fall-to-fall year.

The fall-to-fall year thus allows enough time (6.5 months) and was; therefore, the calendar being used in 2 Kings.

3. Example from Nehemiah

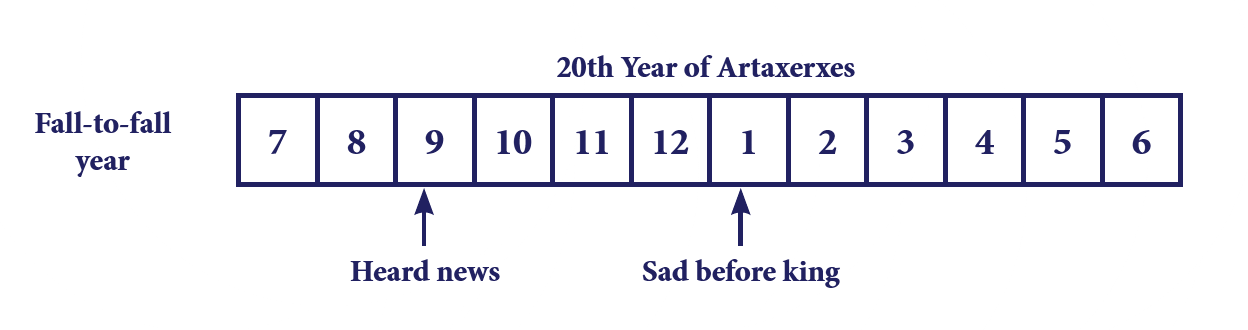

In

In

Nehemiah could not be sad in the first month over news that came to him in the ninth month. But in a fall-to-fall calendar, the problem is solved.

Interestingly, this third example shows that the Jews were here using their own fall-to-fall calendar when speaking about a Persian king. The first two examples were of Jewish kings—Solomon and Josiah. But here, we find that Nehemiah used the Jewish fall-to-fall calendar when speaking of a Persian king. This is really significant since the same is true in Ezra 7.

Now some might object that Nehemiah and Ezra are two different books and that we are not free to say Ezra used a fall-to-fall calendar just because Nehemiah did. In reply, we would point out that in the Jewish Old Testament Canon, Ezra and Nehemiah constituted ONE book known as Ezra-Nehemiah. Unless it can be demonstrated to the contrary, therefore, we must accept that a book would be consistent with itself so that a fall-to-fall calendar is also indicated for Ezra.

Of course, all this evidence is biblical, and some could argue that it is not very convincing. However, Dr. S. H. Horn and Dr. L. H. Wood did research work on papyrus manuscripts found in Elephantine Island in the Nile in Upper Egypt. These manuscripts were later rediscovered in a Brooklyn museum in New York. They are important because they were written in the Persian period, around 422–419 BC, by Jewish soldiers stationed in the fortress there. Their real values lie in at least some of them being dated by two different calendars—the Egyptian and the Jewish fall-to-fall calendar. Here now is evidence from outside the Bible that shows the Jews, even away down in Egypt, were using their own fall-to-fall calendar when they referred to the rule of a foreign king. In this case, it was Darius II.

The details of this evidence have been written up in the book ‘Chronology of Ezra 7’ by S. H. Horn and L. H. Wood.1 Diagrams in this book show how convincing the evidence is. Of particular importance is Kraeling Papyrus No. 6. It is the key one that demonstrates that Jews did use their own fall-to-fall calendar when speaking of Persian kings.

Now then we have established the kind of calendar that Ezra was using in Ezra 7. It was the Jewish fall-to-fall calendar. Now we need to look at how the seventh year of Artaxerxes can be fitted into a BC year scale.

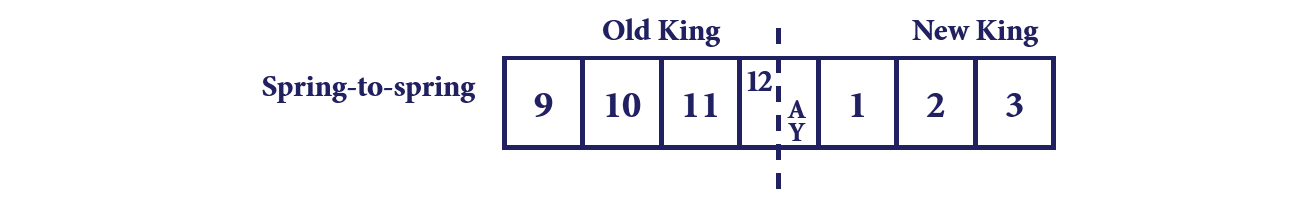

In the time of the Babylonians and Persians, all events were dated in terms of the king’s reign. All documents that bore dates gave the day number, month name, and year number of the current king’s reign. When a king died and a new king took the throne, the remaining portion of that calendar year was considered or called the accession year (

Now, if we add the Jewish fall-to-fall calendar, we have the following pattern:

As can be readily seen, the length of the accession year may be long or short, depending on when the new king came to the throne. It may also be long or short, depending on which of these two calendars is being used.

To construct a succession of kings, all we need to do is discover how long each king ruled. This may be done by using the king lists where they are available. Another method is that used by Parker and Dubberstein in their useful book

We now need to find a way of locking the reigns of these kings into our BC calendar. Archaeologists have found records of many ancient eclipses. They give us the dates they occurred in terms of the reigns of the kings. By using ancient dated eclipses, we can now assign dates to the reigns of these kings. At least one eclipse was actually predicted to take place in the seventh year of Cambyses, and the prediction has been proven correct. This fact speaks for itself about the high standard of astronomical science practiced by these ancient people. When such a tablet is found and translated by an archaeologist, information is then given to astronomers, who calculate mathematically when the eclipse described in that tablet took place. Thus precise dates can be given, and guesswork is eliminated. Babylonian and Persian periods of history are thus among the very best documented periods of history as far as chronological studies are concerned.

The following list gives some of the eclipses for which we have records, especially those concerning the period of history we are concerned in this study .3

| King | Year of Reign | BC Date of Eclipse |

| Nabopolassar | 5th | 22 April, 621 BC |

| Nebuchadnezzar | 37th | 4 July, 568 BC |

| Cambyses | 7th | 16 July, 523 BC |

| Darius I | 20th | 19 December, 502 BC |

| Darius I | 31st | 25 April, 491 BC |

With such a wealth of information regarding the chronology of this period, we can now turn to the question of the dating of the reign of Artaxerxes with confidence, knowing that the seventh year of his reign was mentioned in

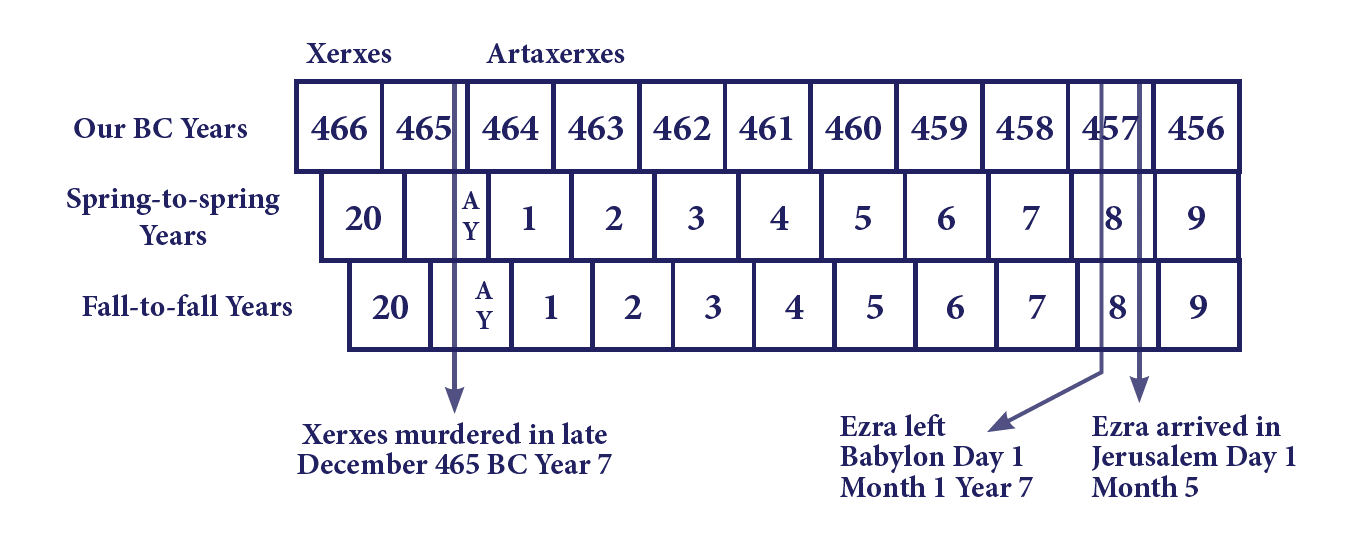

Xerxes, the predecessor of Artaxerxes, was murdered sometime between December 17, 465 BC and January 3, 464 BC. The last tablet dated to the reign of Xerxes bears the date of the twenty-first year of his reign and the ninth month of that year. The first known date for Artaxerxes is from the Elephantine Papyri records in Egypt, and in our BC dating scale is third January 464 BC.

Since this date comes from Egyptian records, most scholars will agree that Xerxes died before the end of December, as it is hardly likely that news of his death would travel from Persia to Southern Egypt in three days.

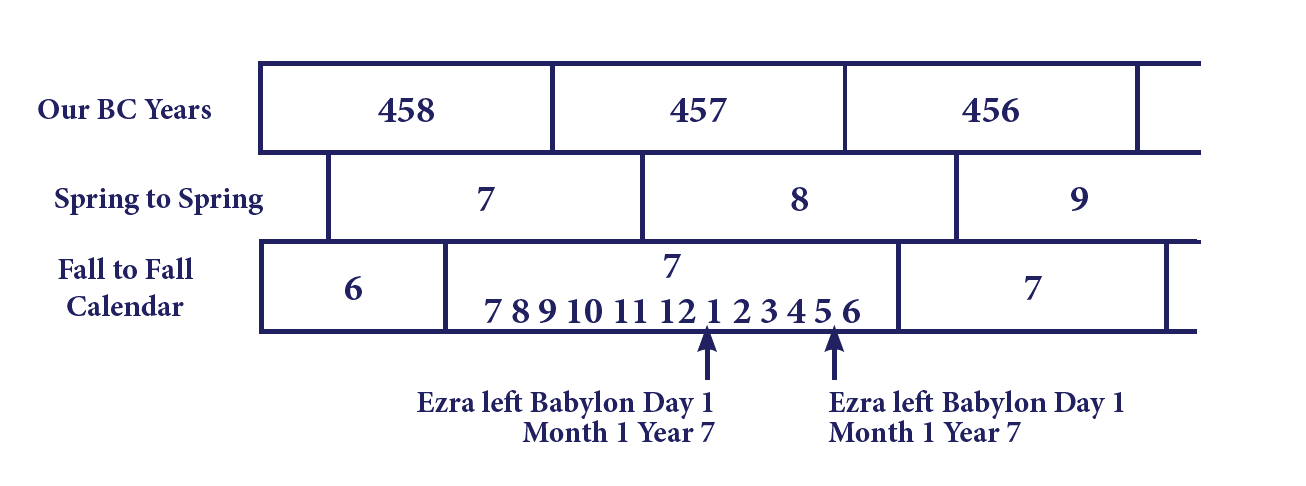

Thus it appears certain that Xerxes’ death must be dated in late December 465 BC. With this information, we can now construct a timeline for the early years of Artaxerxes and thus arrive at the all-important seventh year of his reign. Remember that we calculate that year according to the Jewish Fall to Fall calendar and that the order of months in the fall to fall year run

Note:

The vital seventh year is shown below in enlarged form for clarity.

When these two dates found in

It is interesting to note that William Miller and his associates used a different method for calculating the seventh year of Artaxerxes. They based their work on Ptolemy’s Canon and came up with the same date we have arrived at above. This certainly is gratifying reassurance of the demonstrable trustworthiness of our position.

This study should help to reassure our faith in the message we bear to the world. As the apostle Peter declared

_______________

Horn, S. H. and Wood, L. H. The Chronology of Ezra 7. Washington DC: Review and Herald Publishing Association USA 1953.

Nichol, F. D. Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary, vols. 3-4. Washington DC: Review and Herald Publishing Association, Washington D.C. USA, 1954.

Parker, Richard A and Dubberstein, Waldo H. Babylon Chronology 626 BC-AD 75. Providence Rhode Island: Brown University Press, 1969.

Thiele, E. R. The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. Exeter, Devon England: Paternoster Press, 1965.

Tolhurst, L. P. “Establishing the Date 457 BC,” in Ministry Magazine. April.

Washington DC: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1988.

Wiseman, D. J. Chronical of the Chaldaen Kings (626-556 BC). In the British Museum, Trustees of the British Museum, London, England, 1961.

__________

1 Seigfreid H. Horn and Lynn H. Wood, The Chronology of Ezra 7, Washington DC: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1953.

2 Richard A. Parker and Waldo H. Dubberstein, Babylon Chronology 626 BC-AD 75, Providence Rhode Island: Brown University Press, 1969.

3 Edwin R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings, Exeter, Devon England: Paternoster Press, 1965, p. 218.