P. David Merling

The word “Pentateuch” is the scholarly name for the five books of Moses: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. The name is derived from two Greek words, which simply translated mean “five books.” Unfortunately, there is no specific biblical statement that unequivocally states who authored the Pentateuch. However, Jewish and early Christian traditions both attributed the Pentateuch to Moses. The first-century Jewish historian Josephus, for example, speaking of the books of the Old Testament says, “Five belong to Moses, which contain his laws, and the traditions of the origin of mankind till his death.”1

The liberal or historical-critical view – While Jews and Christians until the nineteenth century believed that Moses was the author of the Pentateuch, historical-critical scholars for the past two hundred years have taught that the books of the Pentateuch were compiled from a number of different sources. For example, because of a number of so-called “doublets,” i.e., two different accounts of the same story in the Pentateuch (e.g., two creation accounts in Genesis 1 and 2), they believe that whenever we find doublets of the same story in the Pentateuch they were written by two different writers.

These scholars believe that different authors of the books of the Pentateuch used different names for God. Hence they refer to one author as the Yahwist because he used the name Yahweh (Gen 2:5; 7:1). He supposedly wrote in the ninth century BC Another author is called the Elohist, because he used the name Elohim (Gen 1:1; 6:2); he wrote a hundred years after the Yahwist, it is claimed. The book of Deuteronomy is attributed to a writer in the time of Josiah (seventh century BC) and much of Leviticus and other “priestly material” is thought to have been written by priests of the temple in Jerusalem in the sixth and fifth centuries BC There is by no means agreement among these scholars as to who wrote what and when, and many different hypotheses have been developed over time.2

These hypotheses have repeatedly been shown to be largely speculative and out of harmony with what we know about ancient Near Eastern literature. Many Christians, therefore, continue to hold to the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch.3 As we will show below, the biblical evidence supports this view.

The witness of the Pentateuch itself – Within the Pentateuch, the only individual who is said to have written anything for future use, besides God Himself (Exod 34:1), was Moses (Exod 24:4; 34:28; Num 17:2, 3; Deut 31:9; 31:22). In addition, God commanded Moses to write information in a book (Exod 17:14). Thus, toward the end of the Israelite wanderings the “Book of the Law” was available for reference, warning, and direction (Deut 28:61; 29:20, 21; 30:10; 31:26).

That the first five books of the Bible belong together, as a unit, is clear within the books themselves. The book of Genesis starts at creation and ends with Joseph, its last hero, dead and buried in Egypt (Gen 50:26). This turn of events is shocking, given the multiple promises made to Abraham that he and his seed would inherit Canaan (e.g., Gen 13:15; 15:18; 17:8). No ancient Near Eastern reader would have been happy to find their hero buried and abandoned in a foreign land, much less when the story line promised the reader and their ancestors their own homeland. Such an unfulfilled ending demands the question, “What happened next?” The Exodus event is the partial answer to the questions of Genesis. On the other hand, the book of Exodus provides its own drama with the spectacular bonding of the Israelites to Yahweh by the Mount Sinai covenant. Yet Exodus does not conclude the story of Joseph’s bones, which were carried out of Egypt with the Israelites (Exod 13:19), and, additionally, the book of Exodus creates its own questions regarding Israelite worship. In the last section of the book, Exodus describes the assembly of the Israelite tabernacle, but the reader is told few details about the worship of Yahweh, which the stories of the book of Exodus imply (consider the problem of the golden calf and the subsequent punishment, Exod 32). Without the fuller details of Leviticus one might be confused as to why the golden calf did not fit within the Israelite system of worship. In addition, when the Exodus account ends, the “glory of the LORD” and the tent of meeting is left in the wilderness (Exod 40:34-38).

That Moses was preeminently prepared to author a work such as the Pentateuch is witnessed by the following qualifications:

(a) Education: “At the court of Pharaoh, Moses received the highest civil and military training” (PP 245; Acts 7:22). This undoubtedly included the skill of writing.

(b) Tradition: He received the traditions of the early Hebrew history, and while tending the sheep in Midian he wrote the book of Genesis under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit (PP 251).

(c) Geographical familiarity: Moses possessed an intimate knowledge of the climate and geography of Egypt and Sinai as displayed in the Pentateuch.

(d) Motivation: As the founder of the nation of Israel, he had a great incentive to provide the nation with concrete moral and religious foundations.

(e) Time: Forty long years of wandering in the Sinai wilderness provided ample opportunity to write the Pentateuch.

Leviticus picks up the story where the book of Exodus leaves it, in the wilderness, at the tent of meeting, and spends most of its chapters explaining the holiness and duties of the priests in the worship of Yahweh. The book of Numbers finds the Israelites still in the wilderness and Moses in the tent of meeting (Num 1:1). Much of Numbers recounts this journey, interspersed with ceremonial issues (e.g., Num 29–30), which one would expect arose while on the journey, ending with preparatory issues regarding appropriating and properly living in the Promised Land. All said, at the end of the book of Numbers, the Israelites are camped in Moab across from Jericho, which lies at the edge of the Promised Land. From this vantage point, Moses’ sermon (Deuteronomy) is most appropriate: a repeating of their story, a plea for faithfulness, and a final farewell. While he preached his Deuteronomic sermon, one can almost visualize Moses with the scroll of the Pentateuch in one hand and his other hand outstretched, pleading for faithfulness from the Israelites.

With the addition of some details in the book of Joshua, the story of the Israelites (i.e., leaving their homeland, serving as slaves in a foreign country, saved by a mighty Exodus from Egypt, bonded to God by the covenantal experience, wandering in the wilderness, and claiming their homeland), begun in the Pentateuch, is complete. Even the question of what happened to the bones of Joseph is settled (Josh 24:32). No part of this Israelite story, nor any book of the Pentateuch, could be left out without affecting the sense and completeness of the overall story of Israel’s origins.

Thus, the most likely reason that the Pentateuch is divided into five books is its topical and historical settings and not a variety of authors. In its totality it is one story by one main author. That the writer largely ignored the issue of authorship implies that everyone knew who the author was when the work was completed. Indeed, had the work been a forgery, then the false claims would certainly have been clearly produced.

The witness of the book of Joshua – One of the strongest evidences that Moses is the author of the books of the Pentateuch is suggested by the omnipresence of Moses in the book of Joshua. Over fifty times in its twenty-four chapters the book of Joshua connects Moses with the commandments or law of the LORD (Josh 1:1, 3, 5, 7, 13-15, 17; 3:7; 4:10, 12, 14; 8:31-33, 35; 9:24; etc.). After the death of Moses God said to Joshua:

Only be strong and very courageous; be careful to do according to all the law which Moses My servant commanded you; do not turn from it to the right or to the left, so that you may have success wherever you go. This book of the law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall meditate on it day and night, so that you may be careful to do according to all that is written in it, for then you will make your way prosperous, and then you will have success (Josh 1:7, 8).

Among other things, these verses suggest that Joshua had ready access to the “Book of the Law,” which means that what Moses had written was for Joshua’s (and future leaders’) ready reference. The command that the words were not to depart from his mouth (Josh 1:8) obviously means that he was to study continuously the writings of Moses as a guide for His decisions as leader and teacher of Israel.

In the books Exodus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, which show Moses leading Israel, Joshua is present to witness the contribution of Moses to Israelite law (Exod 24:13; Num 27:22, 23; Deut 34:9). If there was any doubt as to Moses’ contribution, Joshua, after the death of Moses, could have provided the clarifying details. Yet with the many references to Moses in the book of Joshua, the reader is struck only by the unanimity of the book of Joshua’s appeal to Moses as the writer of the law. So the most knowledgeable expert about the writings and authorship issues of the Pentateuch was Joshua, an eyewitness to many of the events described in the Pentateuch as they occurred and the one whom God challenged to study carefully the Pentateuch. The book of Joshua is also the book with the largest number of references to Moses and the Pentateuch.

The witness of the rest of the Old Testament – The emphasis on the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch is continued in the rest of the Old Testament. The editorial voice of Judges ties the commandments of God to the writings of Moses. God used the surrounding nations “for testing Israel, to find out if they would obey the commandments of the LORD, which He had commanded their fathers through Moses” (Judg 3:4).

The writer of Judges saw Moses as the only writer who provided “commandments of the LORD” and whose work was authoritative enough for God to use as a test. Such sentiments are also found in Kings and in the other books of the Old Testament (1 Kgs 2:3; 2 Kgs 14:6; 21:8; Ezra 6:18; Neh 13:1; Dan 9:11; Mal 4:4). Again, it cannot be over-emphasized that no other writer, other than Moses, is tied to the books of the Pentateuch.

The witness of Jesus and the disciples – Jesus plainly connected Moses with the Pentateuch. By New Testament times, the Jews had divided the Old Testament into three major sections: the Law (i.e., Pentateuch), the Prophets, and the Writings. Jesus acknowledged these divisions: “Now He said to them [the disciples], ‘These are My words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things which are written about Me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms (the first book of the Writings) must be fulfilled’“ (Luke 24:44). On another occasion, to an astonished audience, Jesus said, “Did not Moses give you the Law, and yet none of you carries out the Law?” (John 7:19). In addition, Jesus quoted from four of the Pentateuchal books, while making reference to Moses as their author (See Mark 12:26 and Exod 3:6; Mark 1:44 and Lev 14:1-32; John 6:31, 32 and Exod 16:4; Mark 12:19-26 and Deut 25:5).

The disciples and the early Christian church followed the lead of Jesus, noting Moses as the author of the Pentateuchal books (Luke 2:22; John 1:45; Acts 3:22; 13:39; 28:23; Rom 10:5; etc.). There is no hint from them that any other writer is known for the Pentateuch. For a discussion of who wrote Deuteronomy 34 see page 185.

Summary – The Pentateuch implies that Moses was its author. In addition, Joshua, who was a witness to the Exodus and the events following it, gives credit to Moses for what was written in the Pentateuch. The rest of the Old Testament follows Joshua’s lead. Jesus Himself and His disciples also credit the authorship of the Pentateuch to Moses. Therefore, the conclusion that must be reached, using the biblical materials as our guide, is that Moses was the author of the Pentateuch.

1 Josephus Against Apion 1:39.

2 A useful summary of the various theories is given by Josh McDowell, The New Evidence That Demands a Verdict (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1999), 391–454.

3 Modern biblical scholars who defend the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch include: Kenneth A. Mathews, Genesis 1–11:26, The New American Commentary (Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman, 1995), 24; and Bruce K. Waltke with Cathi J. Fredericks, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2001), 21–29.

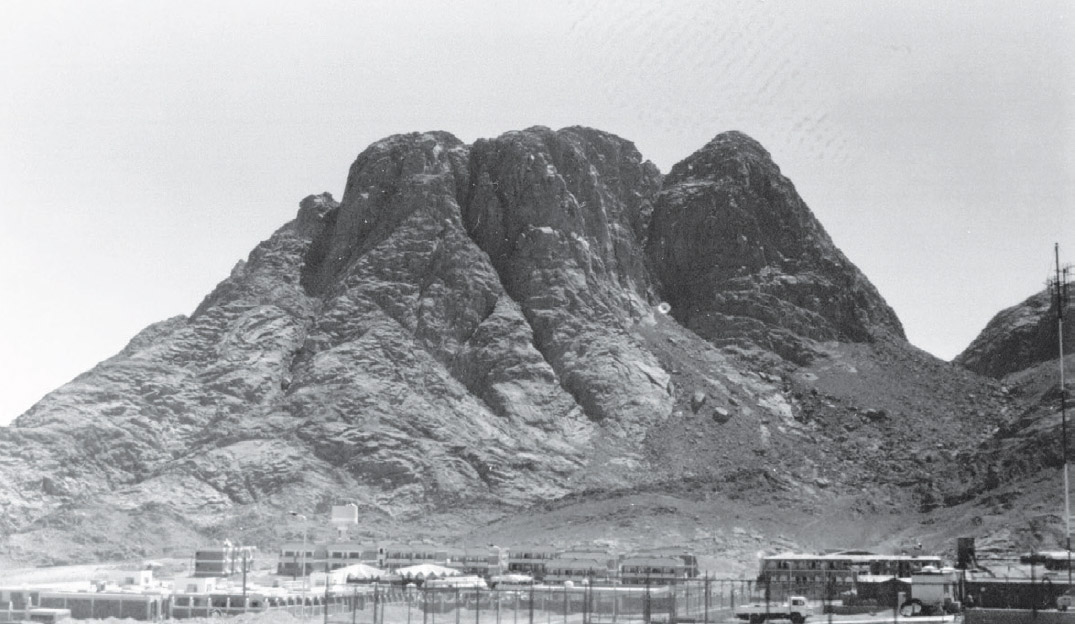

Mt. Sinai