Jiří Moskala

The LORD spoke again to Moses and to Aaron, saying to them, “Speak to the sons of Israel, saying, ‘These are the creatures which you may eat from all the animals that are on the earth.’“ Leviticus 11:1, 2.

Two main objections are given against the observance of the Mosaic dietary laws regarding clean and unclean food: (1) choosing only the uncleanness of animals and neglecting other uncleanness laws, e.g., the uncleanness of women (Lev 12) is arbitrary; and (2) it is claimed that the New Testament explicitly abolishes the laws of clean and unclean dietary regulations. Thus, many Christians believe that they are under no obligation to observe these food regulations.

The uncleanness of animals – In response to these objections a number of reasons exist to demonstrate the continuing validity of the dietary instructions:1

1. The principal rationale behind the distinction between clean and unclean food is that God is holy and He calls His people to holiness (Lev 11:45; 1 Pet 1:15, 16).

2. A comparative study of different kinds of uncleanness in the Pentateuch indicates that the impurity of animals is of a unique category. The two basic categories of uncleanness can be differentiated in the following ways:

a. The type of uncleanness of unclean animals is permanent, natural, hereditary, non-cultic, and thus universal (Gen 7:2, 3; Lev 11:1-47; 20:25, 26; Deut 14:3-21), while the other kind of uncleanness is acquired, temporary, and ceremonial (Lev 5:1-13; 11:24-40; 12:1-8; 13:1-46; 15:1-33; 16:26-28; etc.).

b. The impurity of unclean animals is not contagious. Animals cannot cause or transmit uncleanness. No living unclean animal belongs to the six sources of contagious uncleanness: carcasses, corpses, various skin diseases, mildew, and sexual discharges (blood or semen).

c. Touching or carrying an unclean animal does not result in exclusion from social or religious activities, such as visiting the temple or worshiping in the sanctuary.

d. There is no provision for making unclean animals clean. There is no remedy for the removal of this type of uncleanness; it is impossible to cleanse it or cure it.

e. There is no penalty for disobedience against these food prescriptions. However, the absence of a penalty does not mean that they are to be taken lightly. These prescriptions belong to the category of sins that could not be atoned for by rituals in the sanctuary.

f. These dietary laws are not related to the Old Testament earthly sanctuary services or to the visible presence of the Lord (the Shekinah) among God’s people.

g. The origin of these dietary laws is pre-Mosaic (Gen 7:2, 3) and thus much older than the laws concerning other kinds of uncleanness.

h. The dietary regulations in the Pentateuch are also applicable to the stranger and sojourner (Heb. ger). From the whole corpus of uncleanness in Leviticus 11–15, only the dietary laws are applicable to the sojourner via the law of hunting, which was binding on the Israelites as well as on strangers (Lev 17:13; see also Gen 9:4; Lev 7:17, 18).

3. The strong call to holiness in Leviticus is in harmony with Peter’s powerful admonition to holiness for Christians. Peter’s reason for being holy (1 Pet 1:15, 16) is derived from the passage dealing with the Mosaic dietary laws (Lev 11:44, 45).

4. The close connection between dietary prohibitions, warnings against idolatry, and the prohibition against all immoral behavior (all three are called an abomination [Heb. tocebah] Lev 18:22; Deut 7:25; Ezra 9:1) is an indication that these are moral issues that continue in the New Testament era (see Acts 15:20; Ezek 33:25, 26).

5. The Mosaic laws form a mosaic, i.e., a complete, coherent picture. We cannot throw away certain laws simply because they are present in the Pentateuch, e.g., laws against idolatry, prostitution, homosexuality, or incest. The two greatest commandments are also taken from the same source (Deut 6:5; Lev 19:18)!

6. The health aspect must be taken seriously, even though the issue is not only health but also holiness.

The dietary laws are much older than the laws concerning other kinds of uncleanness (Gen 7:2, 3).

7. Unclean food legislation is not abrogated in the New Testament. There is nothing typological or symbolic in the nature of the clean and unclean food regulations that would point to Jesus as their ultimate fulfillment. On the other hand, ordinances related to the ceremonial system lost their validity with the arrival of the reality that they foreshadowed (Dan 9:27; Eph 2:15).

The New Testament and unclean meat – In order to correctly interpret New Testament passages dealing with food instructions, one must differentiate between two Greek words: akathartos, “unclean,” reflects the Old Testament teaching, and koinos, “common, polluted,” points to the specific rabbinical concept adopted sometime during the intertestamental period and known as defilement by association. It was believed that if something clean touched something even potentially unclean it would become koinos, i.e., defiled.

Seen from this perspective, Mark 7:18, 192 does not speak about eating unclean food but about eating with defiled hands. Christ contrasts the tradition of the elders with the biblical law and underlines the difference between spiritual and physical defilement. Danger to the purity of the mind/heart is more important than what goes into the stomach.

Peter in Acts 10:14 felt he could not eat of the animals, because even the clean animals became polluted by association with the unclean animals (not a biblical but a rabbinic teaching). God asked Peter to stop calling clean animals koinos, i.e., defiled by association with the unclean animals. This meant that he (a Jew) had to stop considering himself unclean by associating with Gentiles (see Acts 10:28; 11:12).

Confirmation of the validity of the Mosaic dietary laws may be seen in Acts 15, through the prohibition of eating blood. It is highly significant that the four issues decided at the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15:20, 29) are found in the same sequence in Leviticus 17-18, and all of them are applied to the alien sojourner (see Lev 17:8, 10, 12, 13, 15; 18:26): (1) food offered to idols (Lev 17:3-9); (2) prohibition of blood (Lev 17:10–14); (3) abstaining from the meat of strangled animals (Lev 17:15, 16); and (4) abstaining from sexual immorality (Lev 18:1–30). In light of Leviticus 17:10–14, these apostolic decrees implicitly include the clean and unclean food legislation (see especially Lev 17:13).

Mark 7 does not speak about eating unclean food but about eating with defiled hands.

In Romans 14 and 1 Corinthians 8:10, Paul explains that meat offered to idols is not polluted because of its contact with idols. Association of the food with idols changes nothing, because the idol is nothing. For this reason, he declares that no food is defiled (koinos) in itself (Rom 14:14). Note that Paul does not use the word unclean (akathartos).

Conclusion – It is not arbitrary to take seriously the uncleanness of food, because it is in a different category. No text in the New Testament, when taken in its context, supports the idea that the clean-unclean food regulations have been abolished. Such a position is not tenable or verifiable.

Christians do not earn salvation or gain God’s favor because they observe dietary principles. Doing so is simply an expression of faithfulness to God. By not consuming things our Lord prohibited, humans exercise deep respect for their holy Creator. In this way our tables become silent witnesses for allegiance to our Creator God. Taking seriously His revelation is a celebration of God’s gift of creation.

“It is historically unimaginable to an increasing number of New Testament scholars that Jesus taught against the Torah’s dietary laws” (David J. Rudolph, “Jesus and the Food Laws: A Reassessment of Mark 7:19b,” The Evangelical Quarterly 74. 4 [2002]: 293).

“The break which Jesus brings is not demonstrated in relationship to the fundamental Old Testament doctrine, but in contrast to the formalism of the scribes and Pharisees of his time” (René Péter-Contesse, Levitique 1–16, Commentaire de l’Ancien Testament, 3a [Geneva: Editions Labor & Fides, 1993], 178.

1 For a detailed study, see Jiří Moskala, The Laws of Clean and Unclean Animals in Leviticus 11: Their Nature, Theology, and Rationale. An Intertextual Study, Adventist Theological Society Dissertation Series, vol. 4 (Berrien Springs, MI: Adventist Theological Society, 2000); see also Gerhard F. Hasel, “Clean and Unclean Meats in Leviticus 11: Still Relevant?” Journal of the Adventist Theological Society 2.2 (1991): 91-125.

2 See the article on Mark 7:19 in this volume.

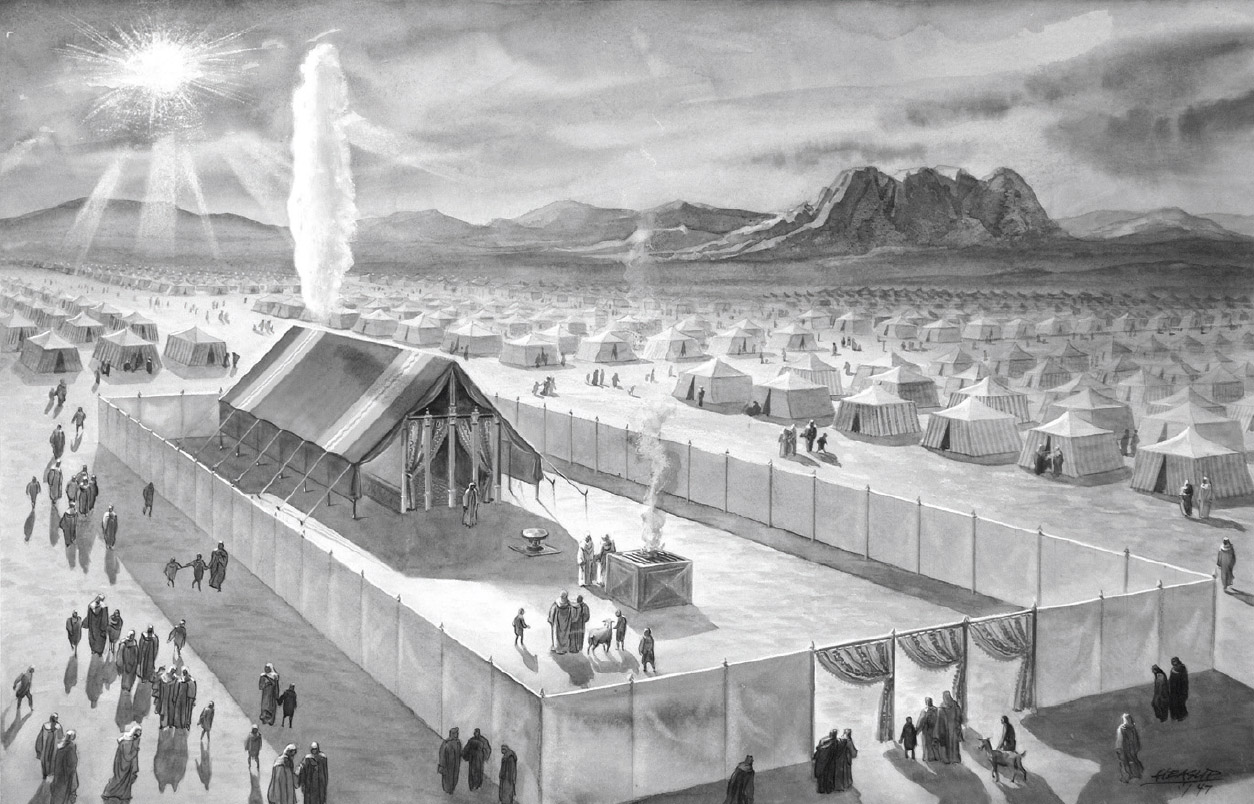

The Old Testament Sanctuary

In the work of Christ for our redemption, symbolized by the sanctuary service, “mercy and truth are met together, righteousness and peace have kissed each other.” (Ps 85:10).

FLB 194